Review: Victorian Artists in Photographs

... and a Very Modern Notion of Fame

I think this review, from 2008, is still revealing as it demonstrates how media-savvy famous Victorians were: conscious of their fame and the need to feed and manage public curiosity through photographs of themselves. Sound familiar?

The initial fascination of this photographic exhibition – at London's Guildhall Art Gallery – is that of most portraiture: it gives the viewer an opportunity to explore the faces, expressions and gestures of those portrayed in the hope of discovering some aspect of the inner person. Victorian Artists delivers this opportunity in spades, for here are the likenesses of: John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George Frederic Watts, John Ruskin, Robert Louis Stevenson, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Ellen Terry, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Charles Dickens, Thomas Carlyle, Whistler, Morris, Burne-Jones and a host of others. With images of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and lesser royals, plus a range of politicians such as Gladstone, Disraeli and Garibaldi, thrown in for good measure.

A secondary fascination comes with reflection on one of the exhibition's persistent threads: that the Victorian public’s thirst for images of the famous was not very different from our own 21st century appetite. The Victorians had no paparazzi, because camera shutter speeds demanded that subjects stood (or sat) still and cooperated. But most of the artists represented here were well aware of their audience, knew the refined and eccentric, sometimes flamboyant, lifestyle that was expected of them, and understood the importance to their careers of feeding and managing public curiosity through photographs of themselves.

Context

Except for a few personal (and more intimate) photographs, these are photos produced by commercial photographers for public consumption – carte-de-visite and presentation prints, some of them from serialised collections such as Living Celebrities and Artists at Home.

‘Photograph’ is interpreted widely, as the majority of prints are photogravures and woodburytypes — which are the products of photomechanical processes that apply the image to paper using a meticulously prepared ‘ink’ solution (as opposed to exposing the image to paper that has been light-sensitised with chemical and metallic solutions). This is photographic print reproduction in its infancy. Despite this many of the images display a fine delicacy that makes them a pleasure to look at. For example, a large woodburytype profile of GF Watts, wearing a velvet skull cap (by Lock & Whitfield) is remarkable for its subtle flesh tones and sharpness of detail — where every hair of the artist’s beard is accounted for. For the chemical purist, there are also albumen, silver and platinum prints.

The exhibition is subtitled The World of GF Watts and is drawn from the Rob Dickens Collection, which was donated to the Watts Gallery in the village of Compton, Surrey. It features images of GF Watts and includes many of Watts’ contemporaries, who would have also fallen within his social circle and be counted as friends. And Watts certainly would have been very sympathetic to a photographic ‘Hall of Fame’. That said, the exhibition can also be easily understood as The World of ... [insert another Victorian artist represented].

Fame

As Victorian artists became more popular, they became wealthier, and with wealth came a heightening of luxury and exoticism in their lifestyles. And (here's a social phenomenon the modern, media-saturated viewer will recognise) the more Victorian artists indulged themselves, the more famous and wealthy they became. Many had grand studio houses built, beautifully and eccentrically decorated. Some artist's opened their homes to the public on an annual basis to help satiate curiosity. Sets of photographs depicting artists in their high-ceilinged, sumptuously appointed studios also became very popular. Artists were usually shown reclined in a good chair, perhaps palette and brushes in hand, surrounded by rows of easels and paintings, their studios teeming with life-sized draped and undraped figures and lines of busts. These photos reveal ‘secret’ interiors sporting lion and tiger skins, oriental carpets, cabinets of materials and shelves of beautiful objets d’art that would do justice to Hello or OK magazine multi-page spreads today. This was the climate in which this exhibition's portraits flourished.

Highlights

A host of ‘artist celebrities’ are represented in the exhibition. Henry Landseer intently peers at us over a sketch pad balanced on his knee, rifle at the ready by his side! The 32-year-old Frederic Leighton leans forward in his chair, restless and dangling his hat, eager to take his leave. In another photo, at the age of 63, Leighton (now Baron Leighton of Stretton and three years before his death) appears in a similar pose but reflective, less angular, with a measure of that earlier energy spent.

There is a great double portrait of John Ruskin and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (by W&D Downey, 1863) standing arm-in-arm – two beau gentlemen taking the air in a London garden. Ruskin, here aged 44, is the indulging elder, while Rossetti, 11 years his junior, is the spoiled enfant terrible. There are a number of Ruskin portraits, including the famous view of him (by TA & J Green) leaning against a holly-topped stone wall at Brantwood wearing a low-brimmed hat and holding a hand-cut walking stick. Another is a wistful Platinotype, taken by Frederick Hollyer, of Ruskin in profile at 75 – still well groomed and firm, but sporting a waterfall beard and exuding the wisdom of Moses.

There is also a curious cabinet size portrait of Rossetti by Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) portraying him as dishevelled and lost, perched awkwardly on the edge of a chair, dressed in acres of houndstooth. Dodgson was clearly much more comfortable photographing children and his other composition here, of Wrothley Russell Ward in a tastefully theatrical play suit coyly posed against a wall, is a trademark example of his work.

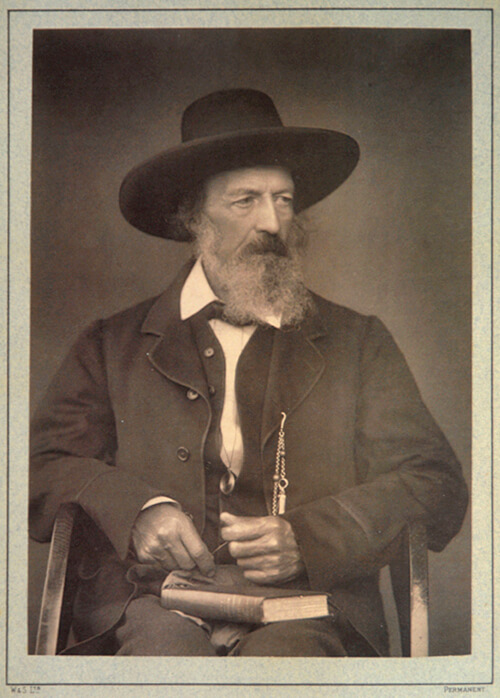

Alfred Lord Tennyson, in a stunning formal portrait by Barraud, sits beautifully draped in supple coat, waistcoat and dark, broad-brimmed hat. He wears a monocle around his neck, ornamented chains hang from his lapel, and a copy of Homer rests on his lap. Tennyson looks to his left, as if evaluating some distant human folly. (Or is it discomfort at the odd, waxed leather treatment that appears to have been applied to his hands?)

Another favourite of mine is the carte-de-visite image of Ellen Terry, finely dressed as Juliet at the Lyceum (1882): poised, confident, and ravishing.

One of the most vibrant portraits in the collection is an albumen print of John Everett Millais in profile (by Herbert Watkins, 1854). Millais set his sights very high, and here is portrayed the engaged, youthful energy that would drive this, arguably greatest, Victorian painter forward through a series of bold styles to achieve his aims and recognition.

I enjoy almost everything Julia Margaret Cameron produced, and out of a pair of works represented here, The Dream (1869) stands out. Modelled by Mary Hillier, this photograph presents us with a woman glowing in light headscarf and cloak, with tumbling hair – like a vision of Little Red Riding Hood – turning away from the viewer to pursue her own private thoughts. But Cameron wishes us to understand this de-focused image as a dream figure, so we are treated to a muse within a muse.

One final, visual feast: the timeless beauty of Margaret Burne-Jones (daughter of the Pre-Raphaelite artist) taken by Henry Herschel Hay Cameron (son of the photographer). This immensely sensitive, painterly photograph seems to perfectly combine the portrait styles and aspirations of painting and photography. And the image casts an interesting illusion, for the young woman’s relaxed pose, open expression and tied-back hair allow us to almost seamlessly merge our modern world with the Victorian.

The Gallery

The Guildhall Art Gallery sits like a rather remote jewel rattled to an unobtrusive corner of the Square Mile. Its collection is unique and rare, but is kept under protective cover and out of the limelight. That is why you will need to actively seek out these Victorian photographic treasures.

Jim Batty

jimbatty.com

Text copyright © 2021 by Jim Batty. All rights reserved.

Photographs are from The Rob Dickins Collection, courtesy Watts Gallery.

Feel free to link to or share this page. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, without signed written permission from the author. A standard publishing fee is payable in advance for any editorial or commercial use.

This review of Victorian Artists in Photographs — The World of GF Watts was originally self-published in 2008. The exhibition appeared:

7 January - 13 April 2008 at Guildhall Art Gallery, Guildhall Yard, London EC2V 5AE

26 April - 13 July 2008 at The Mercer Art Gallery, Swan Road, Harrogate HG1 2SA.